Ancient Malaria Genome from Roman Skeleton Hints at Disease’s History

Genetic information from ancient Roman remains is helping to reveal how malaria has moved and evolved alongside people

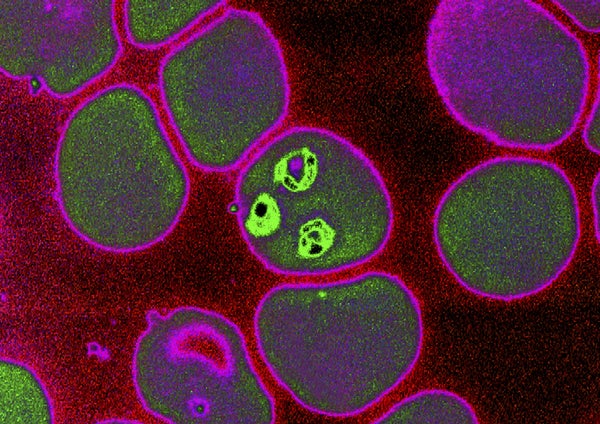

Malaria, an endemic disease caused by hematozoic parasites (Plasmodium falciparum) transmitted by the blood to humans through the bite of the female anophele mosquito.

BSIP SA/Alamy Stock Photo

Researchers have sequenced the mitochondrial genome of the deadliest form of malaria from an ancient Roman skeleton. They say the results could help to untangle the history of the disease in Europe.

It’s difficult to find signs of malaria in ancient human remains, and DNA from the malaria-causing parasite Plasmodium rarely shows up in them. As a result, there had never been a complete genomic sequence of the deadliest species, Plasmodium falciparum, from before the twentieth century — until now. “P. falciparum was eliminated in Europe a half century ago, and genetic data from European parasites — ancient or recent — has been an elusive piece in the puzzle of understanding how humans have moved parasites around the globe,” says Daniel Neafsey, who studies the genomics of malaria parasites and mosquito vectors at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts.

Malaria has long been a leading cause of human deaths. “With the development of treatments such as quinine in the last hundreds of years, it seems clear [humans and malaria] are co-evolving,” says Carles Lalueza Fox, a palaeogenomicist at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology in Barcelona, Spain. “Discovering the genomes of the ancient, pre-quinine plasmodia will likely reveal information about how they have adapted to the different anti-malarial drugs.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of…

Read the full article here