This spring two broods of periodical cicadas will pour out of the ground for a weeks-long stint of mating and egg laying across swaths of the eastern half of the U.S. The bugs are large and loud—but if that’s a grim picture, just consider their emergence instead as nature’s invitation to an all-you-can-eat land-shrimp buffet.

So, with some limitation, it’s okay if your dog or cat chows on a few juicy bites. You’re welcome to do so, too. After all, insects such as cicadas and crustaceans such as shrimp all belong to the same category of animals, called arthropods, which are characterized by their hard outer skeleton. And just like the shrimp that we know and love, the crunchy coating of a cicada hides a tasty nibble of protein—the sort of snack craved by countless animals and even some plants.

“Everything eats insects,” says Julie Lesnik, an anthropologist at Wayne State University. “They are the basic nutritional element that Earth gives us. They are animal-based proteins; they have all of the same benefits as beef but in a tiny, efficient little package.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

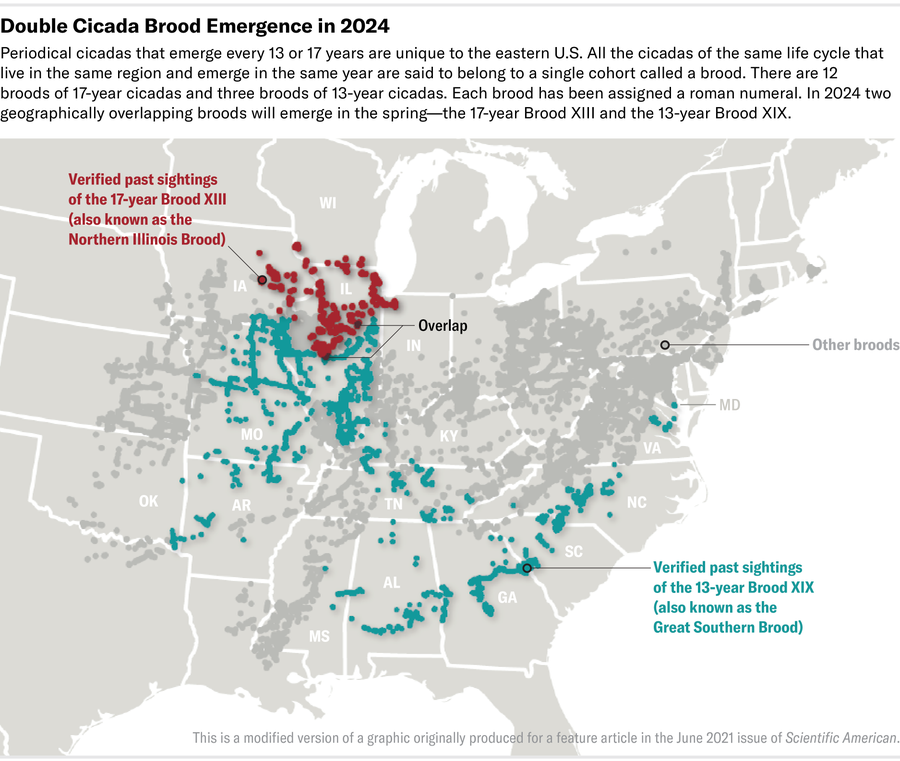

And the seven species of periodical cicadas that call the Eastern U.S. home have another appealing characteristic. Humans rarely see these bugs, which spend 13 or 17 years growing underground, but when they emerge, the insects are practically unavoidable. That’s because cicadas make use of a tactic scientists dub “predator satiety”—they come aboveground in such large numbers simultaneously that not even a forest full of hungry birds, mammals and fish can eat their way through the entire population.

Daniel P. Huffman and John Cooley, modified by Jen Christiansen

Cicadas don’t have many options for self-defense: they…

Read the full article here