How to Move the World’s Largest Camera from a California Lab to an Andes Mountaintop

A multimillion-dollar digital camera could revolutionize astronomy. But first it needs to climb a mountain halfway around the globe

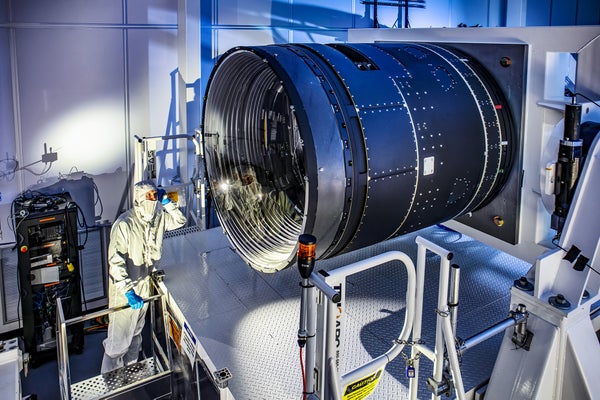

A worker shines a flashlight into the Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s camera.

J. Ramseyer Orrell/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory/NOIRLab (CC BY 4.0)

By late next year, if all goes to plan, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory will have started its 10-year survey of the solar system, Milky Way and galaxies beyond. Its giant eye on the southern skies is a 3.2-gigapixel camera with the size and weight of a small car. By mass and pixel resolution, it is the largest digital camera on Earth. It will scan the cosmos from atop a mountain called Cerro Pachón in northern Chile.

There is just one hitch: the delicate, nearly three-metric-ton machine is currently some 10,000 kilometers away in the hills above San Francisco Bay, where its builders have put it through final tests. In the coming weeks the precisely engineered camera will begin a tense intercontinental voyage in which it will be flown by cargo plane, hauled by truck and painstakingly escorted up twisty mountain roads.

The daunting logistics fall to members of an obscure but consequential engineering subfield dedicated to keeping multimillion-dollar astronomy hardware intact in transit. This is “a very obvious and visible moment when things can go wrong,” says engineer Margaux Lopez of the Rubin Observatory and the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, who is in charge of the effort.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The Rubin camera’s journey begins in a clean room in Silicon Valley, where SLAC will outfit the camera with a steel-and-wire-rope exoskeleton….

Read the full article here