Two ecospecies of Helicobacter pylori — named ‘Hardy’ and ‘Ubiquitous’ — co-existed in the stomachs of modern humans since before they left Africa and were dispersed around the world by human migrations, according to new research.

First discovered in 1983, Helicobacter pylori disturbs the stomach lining during long-term colonization of its human host, with sequelae including ulcers and gastric cancer.

Numerous Helicobacter pylori virulence factors have been identified, showing extensive geographic variation.

In the new study, Dr. Elise Tourette from the Shanghai Institute of Immunity and Infection and colleagues used an unprecedented collection of 6,864 Helicobacter pylori genomes from around the world to investigate the spread of the bacteria.

They unexpectedly found a highly distinct variant of Helicobacter pylori that they termed the Hardy ecospecies, which arose hundreds of thousands of years ago and spread around the world with humans.

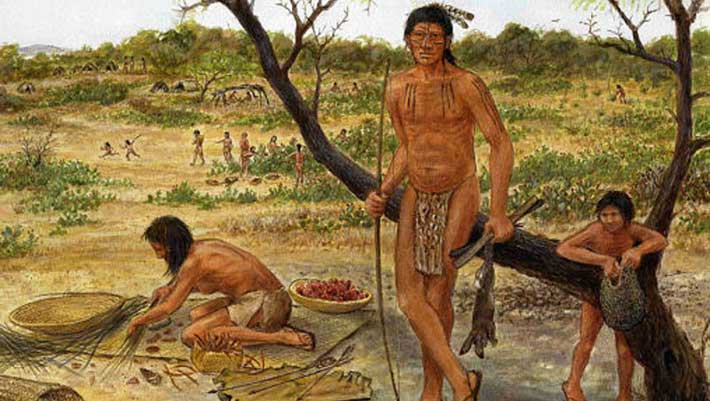

They proposed that the ecospecies is specialized to live in the stomachs of people whose diet principally consists of meat or fish, i.e., carnivores.

Thus, the genetic variation found in the bacteria in our stomachs today can inform us what our ancestors ate.

“Our diverse global sample allowed us to have a better understanding of the history of Helicobacter in humans, which confirmed previous findings that these bacteria were already passengers in our stomachs when we left Africa more than 50,000 years ago,” Dr. Tourette said.

“However, we also identified something surprising, in the form of a new ecospecies of Helicobacter, which we called Hardy.”

“It differs from the common type, which we called Ubiquitous, in more than 100 genes.”

“The Hardy ecospecies turns out to be exceptionally informative about what the bacteria need to do to survive in our stomach, but also, more fundamentally, about how diversity is maintained in bacteria.”

“Most humans living today are omnivores or vegetarians,…

Read the full article here