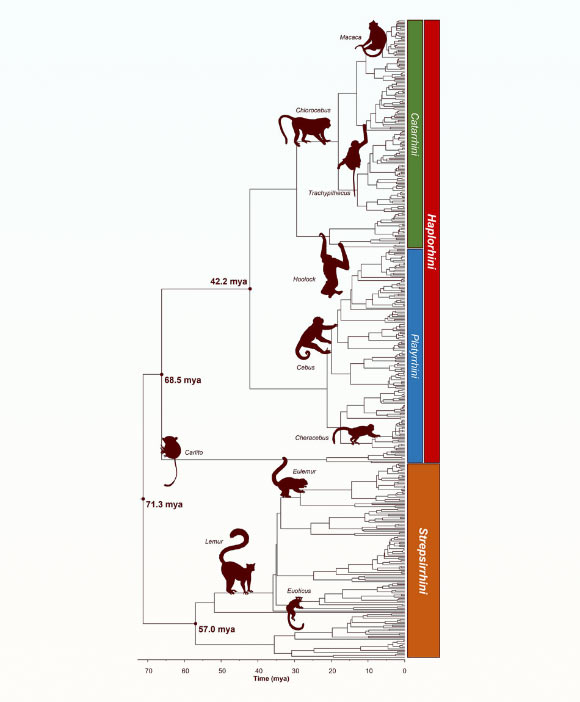

Primates, consisting of apes, monkeys, tarsiers, and lemurs, are among the most charismatic and well-studied animals on Earth.

The mammalian order of Primates comprises 172 species of Old World apes and monkeys (Catarrhini), 146 New World monkeys (Platyrrhini), and 144 lemurs, lorises, and galagos (Strepsirrhini).

Primates exhibit some of the most remarkable behaviors observed in nature; chimpanzees ‘fish’ for termites in hollow logs using specially selected sticks, while orangutans use leaves as gloves to handle spiky durian fruit.

They are some of the most intensely studied species on Earth, and yet there is no comprehensive molecular phylogenetic hypothesis of primate evolutionary history that summarizes the pattern and timing of all primate relationships.

Such a phylogenetic tree would use molecular sequence data to tell us both when each species or group of species first appeared, and which other groups on the tree are their closest relatives.

The largest timed molecular phylogenetic tree of life, called a ‘timetree,’ to date includes just over 200 primate species, while the largest synthetic timetree, drawing from over 4,000 published studies, includes barely double that count, leaving about a fifth of the primate tree of life unresolved.

“The value of timed evolutionary trees containing every species of a given lineage cannot be understated,” said first author Dr. Jack Craig and his colleagues at Temple University.

“While such trees are intrinsically compelling, as they capture the evolutionary history which gave us our present biodiversity, they also form essential foundations for many types of future work.”

“For example, taxonomic and systematic efforts to catalog species rely on them to identify new lineages.”

“Studies of the rate of evolution and its possible correlates like climate and geological changes are fundamentally tied to their underlying phylogenies.”

“Fields like biogeography, phylogeography, and historical…

Read the full article here