We’re all familiar with the sun’s daily motion in the sky. It rises in the east, gets higher in the sky until circa noon, then begins its hours-long descent to set on the western horizon.

You may also know of our star’s more stately annual journey. For Northern Hemisphere dwellers, as summer approaches, it moves a tiny bit higher in the sky every day at noon until the June solstice, when it turns around and starts to get lower every day until the December solstice.

These motions are the clockwork of the sky. They repeat with enough precision that we base our measurements of passing time on them. But there are more than two gears to this cosmic mechanism; in addition, there are subtle and elegant—though somewhat bizarre—cogs that swing the sun’s position in the sky back and forth during the year, as well as up and down.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

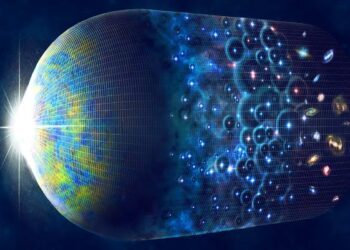

If you were to stand in the same spot every day and take a photograph of the sun at the same clock time (ignoring the shift during daylight saving time), after a full year, the position of the sun would form a lopsided figure eight in the sky. This phenomenon is called the analemma, and it’s a reflection of Earth’s axial tilt and the ellipticity of our planet’s orbit. They combine in subtle ways to create the figure-eight pattern, and the best way to understand all this is to examine these effects separately.

First, what would be the sun’s position in the sky if Earth had no axial tilt and its orbit were a perfect circle? In that case, the sun would trace the exact same path in the sky every day. If you took a daily photograph in the same place at the same time, the sun would always be at the same spot in the sky; the figure-eight analemma would collapse to become…

Read the full article here