Earth’s Moon shrank more than 46 m (150 feet) in circumference as its core gradually cooled over the last few hundred million years, according to a paper published in the Planetary Science Journal. In much the same way a grape wrinkles when it shrinks down to a raisin, the Moon also develops creases as it shrinks. But unlike the flexible skin on a grape, the lunar surface is brittle, causing faults to form where sections of crust push against one another.

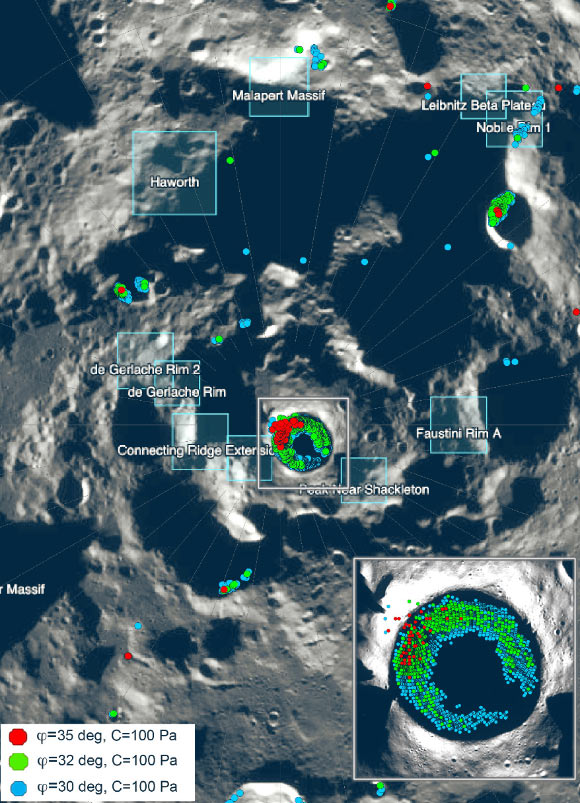

“Our modeling suggests that shallow moonquakes capable of producing strong ground shaking in the south polar region are possible from slip events on existing faults or the formation of new thrust faults,” said Dr. Tom Watters, a planetary researcher at the Smithsonian Institution.

“The global distribution of young thrust faults, their potential to be active, and the potential to form new thrust faults from ongoing global contraction should be considered when planning the location and stability of permanent outposts on the Moon.”

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera onboard NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) has detected thousands of relatively small, young thrust faults widely distributed in the lunar crust.

The scarps are cliff-like landforms that resemble small stair-steps on the lunar surface.

They form where contractional forces break the crust and push or thrust it on one side of the fault up and over the other side.

The contraction is caused by cooling of the Moon’s still-hot interior and tidal forces exerted by Earth, resulting in global shrinking.

The formation of the faults is accompanied by seismic activity in the form of shallow-depth moonquakes.

Such shallow moonquakes were recorded by the Apollo Passive Seismic Network, a series of seismometers deployed by the Apollo astronauts.

The strongest recorded shallow moonquake had an epicenter in the south-polar region.

One young thrust-fault scarp, located within the de Gerlache Rim 2, an Artemis III candidate landing region,…

Read the full article here