Ever since it opened its giant infrared eye on the cosmos after its December 2021 launch, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has found a shocking surfeit of bright galaxies that stretch back to the very early universe. Their brightness—a proxy for their numbers of stars and hence their mass—is deeply puzzling because galaxies shouldn’t have had enough time to become so bulky in such early cosmic epochs. Imagine visiting a foreign land and finding that many of its toddlers weighed as much as teenagers. You might have questions, too: Is the cause of such large children something in the water, or might it instead be that your grasp of human growth is fundamentally flawed? Theorists who pondered JWST’s big, bright early galaxies felt much the same: Was something fundamental amiss in our understanding of cosmology? Namely, was our knowledge of the expansion of the universe following the big bang simply wrong?

The answer, it appears, need not be quite so dramatic.

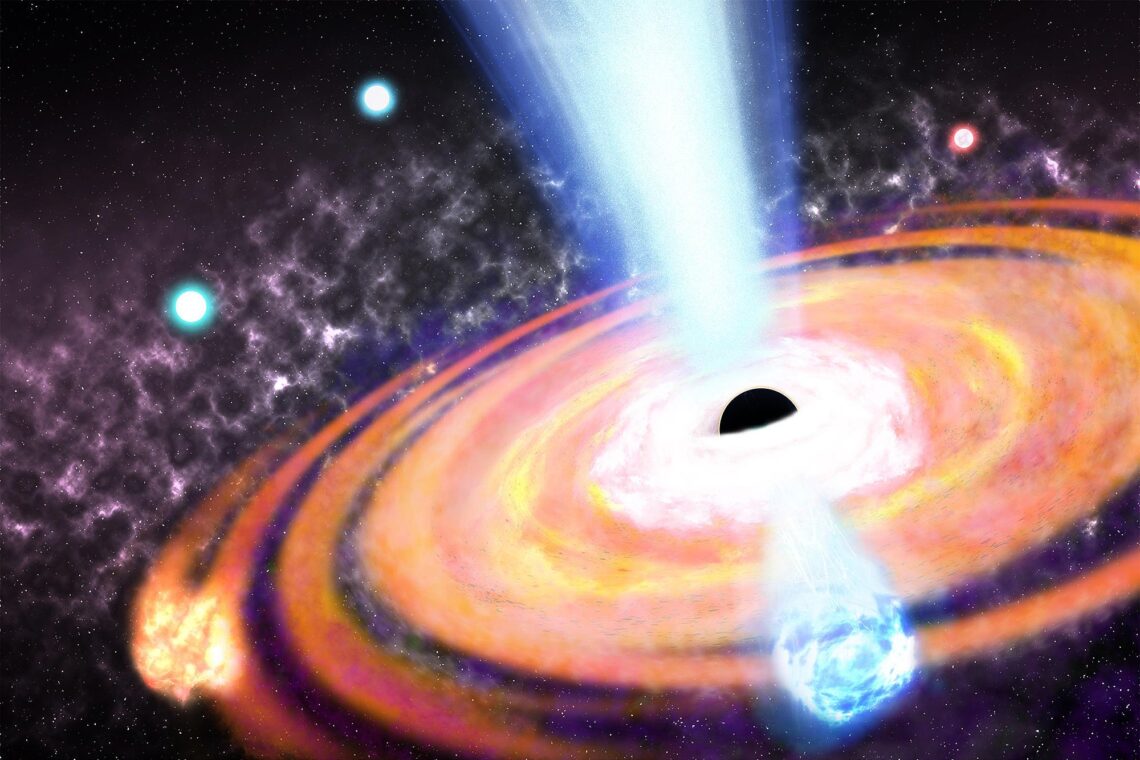

Investigating some of these early galaxies, several studies now point more toward an astrophysical explanation for the unexpected girth—such as earlier-forming black holes or bursts of star formation—rather than some physics-shattering result. “Most people would put their money on the astrophysical explanation right now,” says Mike Boylan-Kolchin, a cosmologist at the University of Texas at Austin. “I’d count myself in that category as well.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Before JWST’s debut, its predecessor, the Hubble Space Telescope, held the record for the earliest galaxy ever found. We see that object, called GN-z11, as it was about 13.4 billion years ago, around 400 million years after the big bang. As soon as JWST turned its gaze onto the…

Read the full article here