Here, count with me: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, T, 11, 12 … Oh, what’s that? You write 10 with “zero”? Fair enough. Zero, we have been told, is the foundation of our number system. Mathematician Tobias Dantzig once called it “a development without which the progress of modern science, industry or commerce is inconceivable.” But that changed in 1947, when mathematician James Foster laid out a system that works like ours in every way — except that it lacks nothing. He called it “a number system without a zero-symbol.”

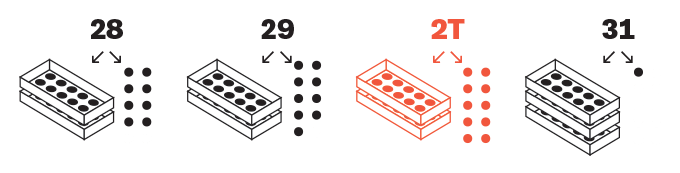

Think of our familiar system as a series of boxes. You can leave up to nine loose objects unboxed. But if a 10th object arrives, you must pack the 10 into a box. When this happens, we use zero to denote an absence of loose objects. The numeral 30 means three boxes of 10, and no additional objects.

This principle continues. For example, in 407, the zero signifies that there are no loose 10s; they’ve all been boxed up as hundreds.

Foster’s system, you might say, asks us to wait before boxing. We leave 10 objects loose, writing them as T. Thus, 30 becomes two boxed-up 10s, or 2T, plus another 10, this one unboxed. (An apter name might be “twenty-ten.”) Only with another object (the 31st) does boxing become necessary.

This way, there are always loose objects — and thus, no need for zero.

Unlike Roman, Maya or Iñupiaq numerals, this isn’t a total reimagining of numbers. Instead, it’s an uncanny parallel universe. Any number without zeros retains its old appearance (1,776 is still 1,776), but any number with zeros is forced to take on a new name.

The numeral 20 becomes 1T (call it “ten-teen”).

Likewise, 106 becomes T6 (10 10s, plus six units; call it “ten-ty six”).

And 3,090 becomes 2T8T (call it “two thousand ten hundred and eighty-ten”).

Weird? Yes. Disturbing? Yes. Logically valid? Again, yes. As Foster noted in 1947, his system challenges zero’s “alleged…

Read the full article here