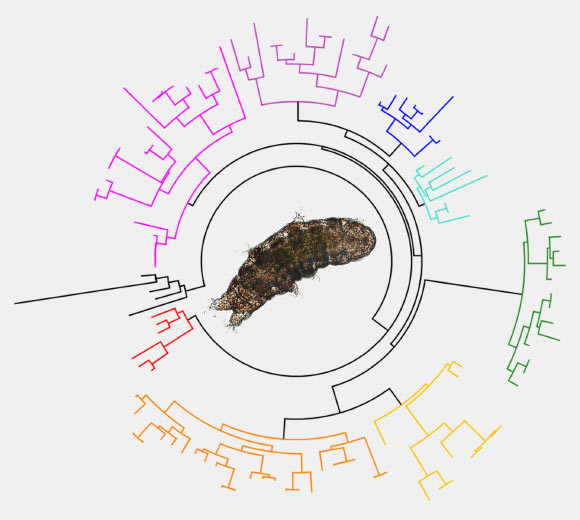

Tardigrades, also known as water bears, can tolerate high doses of radiation, low-oxygen environments, desiccation, and both high and low temperatures under a dormant state called anhydrobiosis, which is a reversible halt of metabolism upon almost complete desiccation. A large amount of research has focused on the genetic pathways related to these capabilities, and a number of genes have been identified and linked to the extremotolerant response of tardigrades. However, the history of these genes is unclear, and the origins and history of extremotolerant genes within tardigrades remain a mystery. In new research, scientists from Keio University, the University of Oslo and the University of Bristol generated the first phylogenies of six separate protein families linked with desiccation and radiation tolerance in tardigrades.

As one form of extremotolerance, tardigrades can survive almost complete desiccation by entering a dormant state called anhydrobiosis (i.e., life without water), which allows them to reversibly halt their metabolism.

Multiple tardigrade-specific gene families were previously found to be associated with this state.

Three of these gene families are referred to as cytosolic, mitochondrial, and secretory abundant heat soluble proteins (CAHS, MAHS, and SAHS, respectively) based on the cellular location in which the proteins are expressed.

Some tardigrade species appear to possess a variant pathway that involves two families of abundant heat soluble proteins first identified in the tardigrade Echiniscus testudo and usually referred to as EtAHS alpha and beta.

Tardigrades also possess stress resistance genes that can be found in animals more broadly, such as the meiotic recombination 11 (MRE11) gene, which has been implicated in desiccation tolerance in other animals.

Unfortunately, since the identification of these gene families, limited information has been available from most tardigrade lineages, making it difficult to draw conclusions on…

Read the full article here