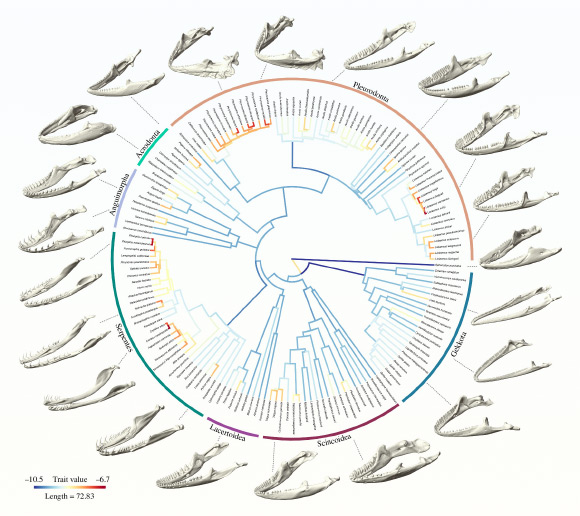

New research led by University of Bristol scientists sheds light on how lepidosaurs — the most diverse clade of tetrapods, including lizards and snakes — have evolved remarkably varied jaw shapes, driving their extraordinary ecological success.

Lepidosauria is the clade comprising lizards, snakes and the tuatara, and with over 11, 000 species, represents the most speciose group of tetrapods today.

Since their origin at more than 240 million years ago, lepidosaurs have diversified into a myriad of sizes and body plans.

Among living species, the range in body size spans three orders of magnitude, as exemplified by the approximately 1.7-cm-long Sphaerodactylus geckos and the approximately 10-m-long green anaconda.

Extremes in large body size become even more dramatic when extinct mosasaurs are considered (up to 17 m in length).

Disparity in body form is reflected in the different degrees of body elongation, and reduction or modification of limb elements seen in multiple lineages, with snake-like body plans evolving at least 25 independent times.

Similarly, lepidosaurs show a rich variety in skull configurations shaped by the loss and gain of skull bones during their evolutionary history, and the acquisition of different kinds and degrees of cranial kinesis.

As a result of this diversification of forms, lepidosaurs have conquered diverse ecological niches across most of the globe.

In the new study, University of Bristol researcher Antonio Ballell Mayoral and his colleagues discovered that jaw shape evolution in lepidosaurs is influenced by a complex interplay of factors beyond ecology, including phylogeny (evolutionary relatedness) and allometry (scaling of shape with size).

In terms of jaw shape, they found that snakes are morphological outliers, exhibiting unique jaw morphologies, likely due to their highly flexible skulls and extreme mechanics that enable them to swallow prey many times larger than their heads.

“Interestingly, we found that jaw shape…

Read the full article here