Location, location

Scientists launched a rocket from Svalbard, Norway, that measured Earth’s ambipolar electric field for the first time. The weak field may control the shape and evolution of the upper atmosphere and may contribute to Earth’s habitability, astronomy writer Lisa Grossman reported in “At long last, scientists detect Earth’s hidden electric field.”

Reader Jayant Bhalerao, a college physics instructor, found the story useful in class: “We will share it with our students, so that they can appreciate how things they are learning in the textbook have real-life applications.”

Bhalerao also wondered why scientists chose Svalbard as the rocket’s launchpad. “Is there perhaps a scientific reason, or is it just infrastructure?”

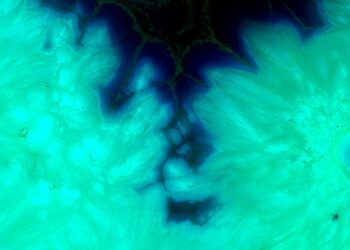

To measure the ambipolar electric field, the rocket needed “to measure the escape of Earth’s atmosphere at the poles, where some of the planet’s magnetic field lines are open,” Grossman says.

“Earth’s magnetic field is kind of like a bar magnet, with field lines running from the North Pole to the South Pole in big closed loops. In these loops, charged particles are kept contained to Earth’s vicinity,” Grossman says. But at the poles, some field lines shoot out into space, allowing charged particles to escape. “The only launchpad that’s far enough north to reach that open magnetic region is the one in Svalbard,” she says.

Measuring mergers

Scientists are becoming increasingly optimistic about the possibility of detecting primordial black holes. If they exist, these ancient black holes born just after the Big Bang may shed light on the mysteries of dark matter, freelance writer Elizabeth Quill reported in “Black Hole Dawn.”

Cosmologists hope to spot signs of primordial black holes by studying black hole mergers, especially those with bizarre features, such as unexpected masses and spins.

Reader Michael Cross asked how scientists…

Read the full article here