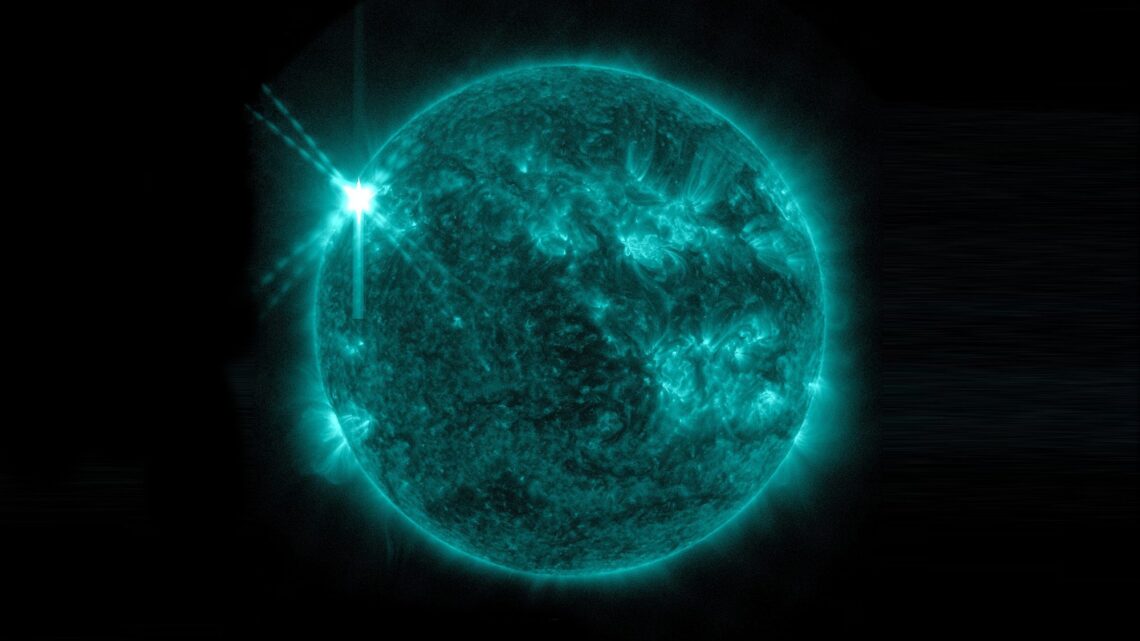

On Friday, February 17, a part of the sun erupted. A piercingly bright flash of light—a solar flare—shone briefly from the left limb of our star, where it was captured in an ultraviolet image by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory spacecraft.

“It wasn’t the largest in history by any means, but it was a significant X flare,” Thomas Berger, a solar physicist and director of the Space Weather Technology, Research, and Education Center at the University of Colorado Boulder. (The “X” refers to the letter grading system of solar flare intensity, which ranges from minor A-class to severe X-class flares. “Solar flares of that magnitude will generally cause some radio-interference on the sunlit side of the Earth for an hour or two,” he says. Ultimately, this one was fairly mild—the most powerful solar flare ever recorded, in 2003, was more than 100 times more powerful by comparison—and did not cause any major problems.

That said, we’re about to enter a more volatile chapter in the sun’s 11-year cycle of magnetic activity. Solar flares are one of three major forms of solar-eruption activity, along with coronal mass ejections and radiation storms, which are likely to increase in frequency over the next few years, according to Berger.

”We are in the rising phase of Solar Cycle 25, and it is expected that activity is going to increase,” he says. (It’s known as Solar Cycle 25 because scientists first began keeping detailed records of sunspots in 1755, and there have been 25 cycles since that time.) The peak of this period, known as the solar maximum, should occur around 2025. The last solar maximum was in 2014.

[Related: How worried should we be about solar flares and space weather?]

That rise in activity that could majorly impact planned space activities, such as the rapidly growing constellations of low-Earth orbit satellites. And a 2025 solar maximum would coincide with NASA’s Artemis III, which aims to return…

Read the full article here