The tall, stony coastlines of the northeast Pacific Ocean are much quieter than they were just a decade ago. Following a punishing marine heat wave in the region, the raucous seabird colonies that once crowded the sea cliffs are now greatly thinned, to a quarter of their former size in some places.

This abrupt loss of millions of birds, and probably many other animals, may be the largest wildlife mortality event recorded in modern times, researchers report in the Dec. 13 Science.

“We knew [the population decline] was big, but the numbers are a gut punch,” says Heather Renner, a wildlife biologist with U.S. Fish and Wildlife at the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge in Homer.

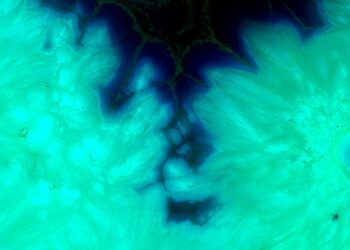

The story begins in late 2014, when a brutal marine heat wave nicknamed the “Blob” parked itself over the Pacific northeast, raising ocean temperatures far above normal for almost two years. The colossal cauldron cooked up an ecological chain reaction, slashing phytoplankton populations and in turn the forage fish that seabirds like common murres (Uria aalge) eat (SN: 1/15/20). In 2015 and 2016, the birds starved to death en masse.

Renner runs a monitoring program spanning the region that has been collecting data on seabirds for the last 50 years. The scale of the toll was immediately obvious.

“We knew right away that it was a big catastrophe,” Renner says. “There were 62,000 carcasses that washed up on the beaches, all over the Gulf of Alaska, all the way down to California. It was clearly a big deal, but we couldn’t really quantify the size of the mortality very well.”

To get a better idea of the full impact on the murre population, the team used colony count data from 1995 to 2022, gathered across 13 colonies along the margins of the Bering Sea and the Gulf of Alaska. After getting bird counts before and after the heat wave, the researchers then extrapolated those results to the entire Alaskan murre…

Read the full article here