If you’ve ever looked up at a mostly blue sky and seen straight white lines criss-crossing the horizon, or watched a plane puff out a plume as it passed above, you may have wondered, “what causes that?” Condensation trails, or contrails for short, are not simply exhaust, like you might see from a car tailpipe (though they’re similar). And no, they’re also definitely not “chemtrails.”

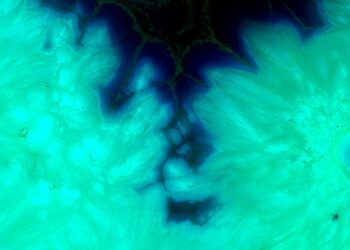

What they are, instead, is frozen water vapor crystallized on soot particles, both of which are standard byproducts of a jet’s combustion engine. In brief “a contrail is an artificial cloud,” says Stephen Barrett, an engineering professor at Cambridge University who studies the environmental impacts of aviation. “They’re very much the same as natural cirrus clouds, except they’re initially long and straight,” he tells Popular Science. And though conspiracy theories about airplanes distributing mind control chemicals aren’t correct, contrails are having a negative planetary effect.

How do contrails form?

Despite being as simple as water vapor and dust, contrails don’t always form or linger in a plane’s wake. Atmospheric conditions have to be just right to enable the jet vapor to crystallize: moist enough that the water doesn’t evaporate, and cool enough that it freezes. “Air that’s cold enough or humid enough is called ice supersaturated,” says Barrett.

Compared with other atmospheric elevations, ice supersaturation is relatively common at standard commercial jet cruising altitude (about 35,000 feet up). Yet still, it only happens about five to 10 percent of the time, he adds.

The length of time a contrail lasts, or its “persistence” is also dependent on conditions. Warmer and drier air often means they’ll dissipate in a matter of seconds or minutes–but the right recipe of cold and wet can leave contrail clouds sticking around for up to six hours, spreading wide across the sky, Barret explains.

Because…

Read the full article here